It happened again the other day, at it has so many times in the last few months. And it will happen again, I have grown to accept, until, well, until it finally doesn’t.

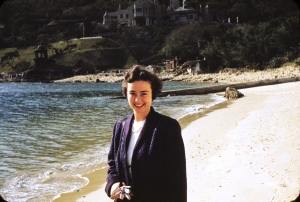

I reached for my phone, an instinct rooted in countless repetitions across my life, to call my mother. She’ll know the answer, I was certain, to whatever small question I was considering about a recipe, or a plant, or the identity of some distant connection in our family. In the age of over-abundant digital information, where some have never touched a cookbook or handwritten family recipe and turn instead to the words of distant strangers, I still trusted my mother’s knowledge, experience, and judgment on certain topics above all options. Besides, it was a reason for a chat. It was a chance to hear her voice, to hear “love you, too, sweetie,” one more time.

In the more than nine months since my mother died, I’ve thought about calling her dozens of times. At first, my hand might even reach toward the phone on the kitchen counter before I caught myself. Nine months into the grief journey, memory at last overcomes instinct before I look for the device, but the inclination still keeps coming. I asked a beloved friend who lost someone the year before Mom died how long this pattern would go on. “Until it doesn’t anymore,” she replied, with a sad, knowing shrug.

The phone call instinct hit me again when I contemplated a summer tradition during our first summer without Mom. As far back as I could remember, she undertook the project every summer until she no longer had her own kitchen. A second or two later, still stinging from that urge to call, I reached instead for a small binder on my cookbook shelf, a little loose-leaf number she made for us with copies of recipes from family and friends she wanted to be sure she preserved.

I’d never checked the binder for applesauce hints. After all, we’ve made it every summer for years, first under her direct supervision, then from memory of her guidance when working in the kitchen was no longer easy for her. In truth, I didn’t really have any lingering questions about the relatively simple process, but I wondered if seeing her notes might help me make my way into the kitchen and get started. How funny to realize that this perennial favorite was not included in her compilation. Maybe she thought it was too obvious and simple to write it down; who knows?

So, with nothing to guide me but memories and a daughter’s fear that I would let Mom down if our family moved through a holiday season with no applesauce on the table, it was time to get busy. Making applesauce is a fun and pretty labor-intensive afternoon in the kitchen with a team of like-minded helpers. Over the decades, my mother made it with her mother, one of her aunts, her children, then her grandchildren. But company in the kitchen this time was not for me. Uncertain how it would feel with the grief still so fresh, I undertook it alone. I wondered what memories it would invoke, and how it would feel to revisit them. Deep down, I hoped it maybe it would help. And there was also the opportunity to honor Mom’s habit of giving away her bounty to the sick or the sad, those in need of comfort food, or as a simple gesture of thanks.

Alone in the kitchen with the gorgeous green apples, knives and cutting boards, the saucepan and the mill, I got to work. Sure enough, as the tart aroma of the cut fruit filled the house, the memories turned my kitchen into a movie theater of the heart, with images and voices moving around as though they were standing at the counter next to me. In memory of those gone ahead who re-appeared to help out that afternoon, here is a faithful description of the process she taught us.

The Very Best Homemade Applesauce

Ingredients and equipment:

½ bushel of Lodi (pronounced Loe-die) apples

Good paring knives and cutting boards

5-quart stove pot

8-10 freezer containers, depending on size you prefer

Foley mill

Step 1: Wash apples thoroughly. Quarter and remove core. Chop quarters into smaller sections about 1-1 ½ inches across; do not peel. Using smaller pieces enables the apples to soften faster on the stove and helps prevent any burning on the bottom of the pan.

Add about an inch of water to the pot. Don’t add too much water, or the sauce becomes too thin. Heat water to near simmering, then begin adding apple pieces. Increase heat to a gentle, ongoing simmer, stirring frequently, on low-medium heat until apples soften and break down. Continue adding additional apples and simmering until mixture reaches desired thickness. Extra water can always be added if needed.

Mom always said that as long as you didn’t burn the apples in the pot, you couldn’t really mess this up. The secret to the whole thing, she said, was choosing the right apples. We always use Lodi, an early summer apple with a distinctive, lip-smacking tart flavor. We don’t add sugar, believing the natural flavor is the secret ingredient. Over years of offering our delicacy to guests, it’s become clear the tart flavoring is not everyone’s thing. Recently I’ve made a second batch using a sweeter apple variety called Paula Red, recommended by the women at Jackson’s Orchard in Bowling Green, Ky, the only folks whose opinions on applesauce I value as much as Mom’s. (Jackson’s is a family enterprise that produces the best apples you’ve ever laid eyes on.) I serve that second variety to friends and save the Lodi batch for family occasions.

Step 2: Pour the simmered apple “stew” into a Foley mill positioned above a large mixing bowl. The mill uses an angled blade and the circular motion of the crank to strain the stew into sauce consistency and retains the skins to be discarded. Crank until all stew has been compressed into sauce; let cool before storing. A half-bushel of apples makes about nine quarts. Use or freeze in 2-3 weeks; freezes well for up to a year.

As I chopped, stirred and milled, I let the memories flow around the kitchen as they would. There was Mom’s Aunt Dadie, who cooked with a sensible print cotton apron over her dress, which was always paired with nylon stockings and low-heeled pumps, even in the kitchen. She was Mom’s favorite family cooking companion, competent, fast and focused in the kitchen. There was Mom in my sister Kate’s kitchen the last year she was able to join in the process. She perched on a stool by the stove, also sporting an apron, stirring one pot patiently while I tended another, calmly reassuring her always over-anxious daughter that I was doing just fine, just fine. There was my beautiful niece, sharing memories of her childhood time in her grandmother’s kitchen, mimicking the circular motion of the mill with her right arm and emphasizing, “That’s work!” Finally, there was my own granddaughter, probably about four years old, caught at the Christmas table using both hands to up-end the delicate porcelain bowl (also Mom’s) so she could lick the final smears of applesauce off the bottom.

At the end of a long, hot afternoon in the kitchen with my memories and the visitors they brought along, I filled a freezer shelf and felt some relief that I had done Mom proud. Thanksgiving will be here soon, and we’ll have plenty of applesauce for the family table. Bowl-licking will be encouraged.

A couple of weeks after I finished, a kind neighbor with great handy skills loaned me a tool and expert guidance on how to fix my locked-up sink disposal. When I knocked on the door to return his loan, I offered a container from the freezer. “Homemade applesauce,” I explained. “Thanks so much for helping me out.”

“Oh, great, thanks!” he smiled. “I love applesauce. My mom used to make it.”

“Really?” I answered, surprised that I could keep a catch out of my voice. “Mine, too.”