I noticed the other day that Christmas is back.

The signs were small, but distinct. I went looking for my holiday coffee mugs, grinning as I liberated them from an upper shelf, where they had been imprisoned for four straight calendar rotations of December 25s. Oh, yes, and far back in the dusty, unused section of the closet, there is that bling-y Christmas t-shirt, black with a reindeer outlined in silver sequins (ooh-la-la). A colleague at the office looked up the other day from her screen and smiled when I motored past, unconsciously humming the soul-powering refrain from Oh Holy Night. (Oh, NIGHT, dee-VI-I-NE, oh, oh, night…)

Hahaha, may come the retort, of COURSE Christmas is back. It is everywhere, right? That surging sea of commercial madness, as unavoidable, as intrusive, as omnipresent, as the morning sun in the dawn sky. Where have YOU been, under a rock?

Where I have been is a place where Christmas vanished with apparent finality. Four years ago, my father took his last breath in the early morning hours of December 22, his eyes on my mother’s cherished face. Somewhere far away that morning, a trap door opened, and Christmas fell silently away, vanishing without a whisper, leaving behind an empty, fathomless shadow.

When Mercy is doing her job, memory blurs a great deal about tragedy. Thankfully, there are gaping holes in my recollections of that Christmas. I do remember showing up at the appointed time for the family gatherings already planned, because that is what my mother asked us to do. I also remember two dear friends rushing over to be present that morning, just after the news came. Among other acts of solidarity, they helped wrap my pile of gifts, the Christmas task I always leave for last. I hauled the packages out to the car like a bunch of fallen alien asteroids, existence unexpected, definition and destination unknown.

When Christmas rolled around again, 365 + 3 days after Dad died, I was angry. I stayed out of the stores, away from parties, nowhere close to church. Why should I join in something shrouded in pain? How dare everyone indulge in this endless excess when others are suffering? Only the required shopping was completed, and no decorations hung. Celebrations were shadowy shams for other people, and my own deep faith had not yet moved me to the place where I could again see the Light of Christmas. I thought I never would, when the next year was about the same. I managed a few more routine traditions, mostly for the sake of those close to me, but the Light was still absent.

Fast forward to the present, a few days before the fourth anniversary of Dad’s passing. The coffee is steaming in that mug with the Christmas tree on it, and the schedule includes tonight’s Lessons and Carols service. Christmas melodies cannot be silenced inside my head, where there is no pause button to click.

How did that happen? I wish I knew. So many learned people have studied the psychology and theology of grieving (including some very dear friends), but I can’t pretend to share their insight. I did pursue help when I couldn’t navigate alone, and I certainly learned to respect grief and loss along the way. They are forces that will not be harnessed or controlled, but will march onward with power that is unique to the intricacy and scope of the love that the grief represents.

I long to understand more as I think of a dear friend who lost her life partner unexpectedly a few days ago. Each journey is singular, so no one can pretend to stand in her shoes in these early days of heartache, but I do recognize the crossroads on which her feet are now planted. How we long to comfort those who suffer at this tender time of year. We can listen and offer presence, and to that I can only add my humble testimony that grace and healing are indeed possible, in time. Perhaps it is not for us to know when, or how.

I believe that those we loved and lost play a part in that process. There is no doubt what my father would say, as clearly as if he sat next to me at this table. Never one to preach, he forged his legacy by enjoying life to the fullest, to the very end. So I say aloud, right now: Daddy, my heart is aching. I miss you so much at Christmas. And echoes like these bounce back, in response: “Watch this joke I’m going to play on your mother and see how she laughs. She’s going to love what I got her for Christmas. Can I get you a cocktail? Is the game on yet?”

And so I affirm the empowering words of author Jan Richardson, below:

“It is hard being wedded to the dead; they make different claims, offer comforts that do not feel comfortable at the first. They do not let you remain numb. Neither do they allow you to languish forever in your grief. They will safeguard your sorrow but will not permit that it should become your new country, your home. They knew you first in joy, in delight, and though they will be patient when you travel by other roads, it is here that they will wait for you, here they can best be found where the river runs deep with gladness, the water over each stone singing your unforgotten name.”

Thank you, Lord, for Peace and Light, wherever and however it may be found. Grant comfort to those who need it so much this season. Welcome back, Advent. And Merry Christmas, Daddy.

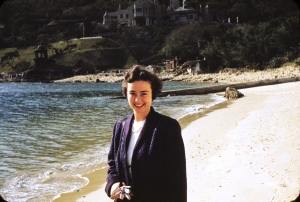

In the cultural tumult of the Sixties and Seventies, when the roles of women changed forever, we so often thought (sometimes rightly, sometimes not) we knew better than the previous generation. I never really wanted a life like hers. While she would be the first to point out she was not born to such things, my mother was, in my eyes, bridge and country clubs, stunning ball gowns and cocktail parties—while I was smoky blues bars, horse barns, jeans and bandanas, and bad boys. Our family of six lived comfortably on my father’s income, while I instinctively knew I would always have to pay my own way. As a working mother, later a single one, I juggled priorities that sometimes seemed a world away from Mom’s daily life, through no fault of either of us. It was easy to assume that my father, in our traditional family structure of the era, was the tough one in the family.

In the cultural tumult of the Sixties and Seventies, when the roles of women changed forever, we so often thought (sometimes rightly, sometimes not) we knew better than the previous generation. I never really wanted a life like hers. While she would be the first to point out she was not born to such things, my mother was, in my eyes, bridge and country clubs, stunning ball gowns and cocktail parties—while I was smoky blues bars, horse barns, jeans and bandanas, and bad boys. Our family of six lived comfortably on my father’s income, while I instinctively knew I would always have to pay my own way. As a working mother, later a single one, I juggled priorities that sometimes seemed a world away from Mom’s daily life, through no fault of either of us. It was easy to assume that my father, in our traditional family structure of the era, was the tough one in the family.

Many of us have known those who do not or cannot face such things in the same spirit as my mother, people who are thrown sideways or backward by terribly tragedy and injustice and don’t have the tools within their hearts to recover. The difference between them and people with the personality and faith of my mother is the subject of spiritual study, psychological analysis, genetics, and many other things beyond my scope of understanding. What makes some people brave and spiritually strong, while others struggle? How we all wish the answers were more forthcoming.

Many of us have known those who do not or cannot face such things in the same spirit as my mother, people who are thrown sideways or backward by terribly tragedy and injustice and don’t have the tools within their hearts to recover. The difference between them and people with the personality and faith of my mother is the subject of spiritual study, psychological analysis, genetics, and many other things beyond my scope of understanding. What makes some people brave and spiritually strong, while others struggle? How we all wish the answers were more forthcoming.