In a recent interview about an upcoming movie he produced, Oscar winner Denzel Washington was asked about the support he provided early in the career of the brilliant young actor Chadwick Boseman, who died earlier this year. Boseman, a central character in Washington’s upcoming film release, had openly expressed his gratitude that Washington paid his college tuition, saying “there wouldn’t have been a Black Panther (Boseman’s breakthrough role) without Denzel Washington.”

Washington responded to his interviewer by crediting the great Sidney Poitier for having mentored him early in his own career, then cited a mentor to Poitier in turn. “It’s our job to pass the baton and share what we know,” the actor said. “You can’t take it with you. All you can do is leave it here.”

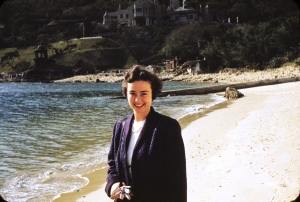

This reflection lingered in my heart as I remember my father during this week that marks the anniversary of his passing in 2013. More specifically, it prompted me to recall a quiet conversation between the two of us late on a Saturday afternoon when he thought his time with us was ending. He had something he wanted me to know before he went.

Dad was scheduled for open heart surgery to repair a vessel that was almost completely blocked and severely limiting heart function. The procedure was less than 48 hours away, early on a Monday morning that we all knew might usher in a new era in our lives. He was 83 years old, had other health issues, knew the risks in surgery were high, and he was thinking about the story of his life.

He took that weekend for reflection, a time he selected with characteristic self-determination, infuriating some of his doting family. When the blockage was discovered just two days before, the cardiologist recommended he stay in the hospital for the weekend, where he could be monitored in advance of the procedure.

“I’m going home,” my father said to the physician. “I’ll see you on Monday.”

“You understand,” the doctor said, sternness overtaking his bedside manner, “that you are at high risk for a heart attack before this procedure. If you have one between now and then, you almost certainly won’t survive it.”

“I’m going home,” Dad repeated. “I’ll see you on Monday.”

Receiving this news at home 200 miles away, I didn’t waste any time. I threw a bag in the car and headed up the road to my parents’ house to make sure I got to talk to him before Monday arrived. I had no idea what, if anything, I needed to say.

But he already knew what he wanted me to hear, when I dashed through the back door into the paneled den, pulling the old maple rocking chair closer to his leather recliner in the corner. He sat where he always sat, with his hands folded, as always, on his belly. How are you doing? I asked tentatively, unsure where to begin.

“I’m doing fine,” he answered, more at peace than I could have imagined for this anxious, driven, intense human being. “You know, no one has had a better life than me. With your mother all these years, and with you kids….no one. I’m a very lucky man.”

There were surely other parts to his thoughts that day as he contemplated his eight-plus decades on this planet, but they don’t survive in memory. Still, I took away that simple statement. The thing he most wanted me to know is imprinted in the mind and heart as clearly as if it was tattooed on my forearm for always: He faced death in a spirit of gratitude for the gifts he was given—or, at least, he wanted us to know he did–with no gift more predominant than his family and the love he had cherished in his life. Of course, the fact that my father loved my mother and all his family was not news; he spoke of love often in our house. What carved this particular declaration so deeply in memory was that he carefully chose it to illustrate the closing chapter of his life.

The morning of the surgery, I was so shaken at the looming prospect that I walked straight into a glass wall separating the surgery waiting room from the hallways leading to the operating suites, drawing hospital staff on the run to check for injuries as I reeled backward and massaged my throbbing forehead. Stunned but not really hurt, I followed my brother and sister into the long, narrow hallway where we could see him roll by. As we walked alongside his surgery stretcher before the OR doors swung open, he looked up at us and said it again: “No one has had a better life than me. No one.”

As it turned out, he survived the heart operation and lived several more months. When the end came, in a different place and for a different reason that none of us saw coming, I don’t know if Dad repeated that affirmation when he said his last words three days before Christmas. But I remembered his earlier declaration then, and I’ve remembered it every Christmas since. It was the final step in his legacy, the shared affirmation that no matter what happened in the future or what challenges history had held, he put gratitude first at the end.

Christmas is on the near horizon again, with another anniversary of his passing and, this year, the presence of global tragedy in our troubled world. As I think of him in the pantheon of emotions that this season holds, it is my job to remember him as he instructed me to, and revisit what he told me, and, as Denzel Washington indicated, to pass the baton. As I edge inexorably closer to the age he was then, I can see and accept that his life was not as easy as it may have appeared, his family as complicated as all families can be, his own demons at times difficult to banish. Still, to borrow Denzel’s phrasing: He did all he could do with what he was given. And at the end, he left it here—with gratitude–for us to remember and share. It was the last, best gift.