It was one of those golden moments, the kind that linger in memory, perhaps more powerful because it was utterly unexpected.

It began with one of those instincts you can’t suppress, because it is rooted deep in your bone marrow. We were gathered around the dinner table, with pizza and birthday balloons and cupcakes waiting and a generally festive atmosphere. My 12-year-old grandson, Buddy, commenced to tell a story involving his younger sister.

“Me and Sis were going to…” he began. I interrupted on autopilot with a correction that, in our family, goes back at least two generations.

“Sis and I,” I corrected, more pointedly than may have been charming at a birthday party.

“Wait, I mean..what?” Buddy stammered, confused. “Why does it have to be Sis and I?”

Before I could open my mouth, his mother raised one eyebrow and beamed a look at her progeny, as if warning off a hopeless punter loading up on a longshot at the race track. “I advise you,” she recommended firmly, “not to get in an argument about grammar with your grandmother. You won’t win.”

And there it was. I’m certain I felt a spotlight illuminating me from above like a soloist on Broadway, with the horns and percussion sounding TAH DAH! Thus arrived the moment every parent longs for: The stunning revelation that something they said, some time, even decades ago, actually penetrated. And stuck.

My daughter was an excellent student, a creative spirit with writing skills far above average for her age, so I rarely reviewed or corrected her English homework. (I had better sense than to touch her math, where I was more harm than help.) That did not prevent me, however, from doggedly correcting her verbal communication from the very early days, starting with the classic, historically festering misalignment of objective and subjective pronouns. Me and Sis? Nope. Not happening.

My mom had ascended to her eternal reward by the time this little birthday grammar episode occurred, but she would have heartily approved. She raised her four children with the same standards, weaving in the correct language—sometimes rather pointedly—around the dinner table and most places the transgressions occurred in the boisterous conversations of four very talkative siblings. It was simply part of the molding of young souls, in her eyes, no different than insisting on clean hair and brushed teeth and responses of “yes, ma’am.”

What drove that habit? Generational patterns, as with so many other things in families. She was raised the same way, the only child of an English teacher whose standards for appropriate and correct speech never wavered. Mom also taught English, just for a couple of years in her twenties in the Philippine Islands when my Dad was stationed at Subic Bay Naval Base. Only history knows if she dogged her students in similar fashion, but when her children began arriving over the next few years, the diligence already had firm root.

Fast forward to the present day, with me now an elder guardian of subject, object, and the like. Will it end with my generation, in our family? Can grammar and clear language survive the age of instantaneous communication? What really matters in the reign of thumb-typing, auto-correct, and shameless comments regurgitated in haste with no punctuation? Should we cave in and rely on the digital editor and her glaring red lines under our errant phrases? Who cares, anymore, about actually knowing grammar?

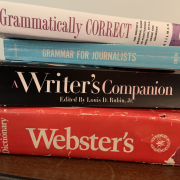

A dwindling few of us still do, though it’s a lonely chair to occupy. My own compulsion to wave this flag is grounded in both family habit and professional training. In my early career as a journalist, editors still cared. They did not take kindly to having to execute grammar corrections under deadline. We had reference books and style guides at our disposal and were expected to be responsible for knowing what was correct. In current times, it’s a rare day there is not a misspelled word or glaring grammar error in headlines and news stories anywhere you can stand to look. Will we ever be rescued from the ubiquitous blizzard of mis-used apostrophes (the Smith’s had a party) and absent hyphens (the sun dappled patio)? I have a favorite t-shirt with this legend on the front:

Let’s eat, Grandma

Let’s eat Grandma

Commas save lives

The heart aches to notice how few people laugh when I wear it.

Still, as the young so often do, Buddy delivered a little glimmer of hope recently. He was probably just looking to get his own back. I was pinch-hitting as driver to his music lesson on a hot day, and he was wearing shorts. I watched as he awkwardly maneuvered his long, lean legs and enormous feet into position as he climbed into the front seat of my car. The speed of his recent growth spurt is still a shock.

He caught me scanning the apparent mile between his hips and knees, and asked, “What are you looking at?”

Nothing, I mumbled, embarrassed to be caught staring. It’s just that you, well, you have a lot of legs.

“No, I don’t,” his pre-teen self replied, with a sly side-eye. “I only have two. If I had a lot of legs, I’d be an octopus, or one of those bugs.”

True! I had to answer, caught crimson-handed and thinking, Touché. Maybe, just maybe, there is hope for the correct sentence, after all.