A drama in one act

The scene

Location No. 1: A 7-year-old girl’s bedroom at about 7:45 p.m. The room is captured in the screen camera’s eye and beamed over the ether to another screen miles away, via the technology that is re-defining communication and relationships in the era of COVID. Child is leaning back against a rumpled mass of pillows, facing the camera, and the lovely pink flowered coverlet is only visible in one tiny triangle in lower left. She is, at least as the scene opens, under a tangle of various layers of covers, accompanied by a large purple bunny squeezed under her left arm, only one, long narrow flop-ear exposed, dangling on top of the covers like a tie adorning a dress shirt. Presumably there is a white dog sharing the bed; only his foot is visible, lower right.

Location No. 2, simultaneously shown: The home office of this child’s grandmother. A stack of children’s books stands at the ready on the work table next to her laptop. Lighting has been carefully arranged to illuminate the pages of the books she will hold up to the camera, but not too bright, because it is bedtime, after all.

The characters

- Sis, the aforementioned 7-year-old girl, who has eagerly accepted her grandmother’s offer to read her a bedtime story via FaceTime.

- Buddy, her 9-year-old brother. Possibly thinks this activity is beneath his age, having largely outgrown his taste for little kids’ books. He is too kindly to say so in front of his grandmother or sister.

- The mother of these children, who plays a role in tech support but does not appear.

- The grandmother of these children, aka G-ma, or Evie, who routinely would never refer to herself as a desperate woman. And yet, she is missing these children so fiercely that she wants to give this strange scenario a legitimate shot.

- A patient, quiet, white and black terrier mix dog named Sam, who never gets far from the children.

- A frenetic but supremely devoted brindle terrier mix named Grace with the delicate presence of an offensive lineman protecting the blind side in overtime of the Super Bowl.

The scene opens as FaceTime connects and G-ma’s face lights up at the sight of the child. Her brother is not visible.

G-ma (brightly): Hi, precious! I’m SO glad to see you. Let’s pick out a book to read.

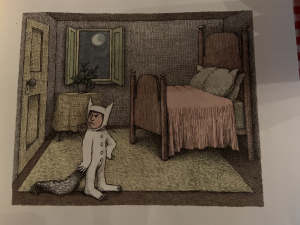

(G-ma holds up a couple of options to the camera. The child is squirming, possibly in anticipation, possibly impatience, possibly both. She sits forward in affirmation and points at the screen when it shows her the cover of the classic Where the Wild Things Are.)

G-ma continues: This one? Great. Let’s get started. Where’s your brother? Does he want to hear this? Buddy, are you there? (Hoping to involve both, she speaks to the child she can’t see.). Do you like this story, too?

(A second face appears on screen, extreme close-up but completely sideways, visible only from the eyeballs up.)

Buddy (non-committal but polite tone): Yeah, but I’ve read it multitudes of times already.

G-ma (flummoxed by this mastery of vocabulary from the sideways, partial face): Did you say multitudes? Is that what you said?

Buddy: Yeah! Multitudes. But it’s OK. You can read it to Sis. (He drops back onto the pillow next to his sister, close enough to be about half visible, then noticeably hoists his own book, his face disappearing behind it.)

Sis (pushing her brother farther away from her on the bed, to gain space and reject his response): Go! Evie, read!

(G-ma begins the old favorite story, turning the pages slowly, twisting in various contortions, attempting to see, while reading, if the pages are visible to the watching child. Striving to keep her audience on the hook, she displays the page where the protagonist is sent to his room for misbehavior)

G-ma : Can you see this? Look at him making that face. What do you think he’s mad at?

Buddy (without lowering his own book, apparently watching over the top of it): He’s mad because…

Sis (shoving him again and interrupting): Stop! You aren’t even reading with us. Go on, Evie. (She turns her back to her brother, propelling herself hard enough to dislodge the position of the laptop, which is now displaying the tranquil bed scene at a 45-degree angle.)

G-ma (uncertain whether to just tilt her own head or request tech support): You knocked the laptop, sweetie. Straighten it back up so I don’t get dizzy looking at you.

Sis: Oh, sorry! (She leans forward to correct the issue but suddenly vanishes, while the screen is filled by the torso of the amber-and-black brindle dog, who has leapt onto the bed and into the action.).

Sis, Buddy, and their mother (simultaneously, shouting out of view): GRACE! GET OFF THE BED!

(Pause. Scrambled audio. G-ma waits, uncertain whether to proceed, thinking this has not gone well. Perhaps it’s too much for the kids to focus in this scenario. They are too young/not interested/just humoring me. Maybe this was more about me, G-ma wonders regretfully. Meanwhile, brindle torso flashes on past and ejects itself out of sight. Grandchildren again visible on camera. Action resumes. Soon, G-ma announces the conclusion is nigh.)

G-ma: Almost done here, guys. Here’s our last page.

Sis (interrupting, directs question to her mother, off camera): Mom, can we do this again? Cause I really like it.

Mother (off camera): Sure, if Evie wants to.

(G-ma reads last page, closes the book.)

G-ma (smiling fondly into camera): Great! That was fun. I love…

Buddy (leaning face sideways into view again, before his grandmother can finish): Thanks! Bye!

(Screen abruptly goes dark. In the ensuing silence, G-ma stares for a second at the black space where the children just were, and then at the cover of the book. She wonders if anything every goes the way it is so brilliantly shown in the grandparenting magazines, with their articles on “10 Ways to Stay Close to Grandkids During COVID.” She doubts it. But knowing she got one vote in favor, she decides to declare victory as she switches off the light.)

THE END