A landmark birthday roared past recently, one of those that bestows a zero digit on your age and thus cannot be ignored. Even for those of us who aren’t given to ruminating about the terrors of aging, it’s hard not to contemplate the implications of the ones that signal a new decade.

Not long before the Big Birthday, my three-year-old granddaughter crawled up in my lap, squirmed into the desired position and happened to shift the wrong way against my stiff right knee. “Ow,” I winced, adjusting Sis slightly. “Be careful, sweetheart. Evie is old.” This last bit popped out unexpectedly; perhaps the zero-digit had been plaguing the subconscious more than I knew. Sis absorbed my reaction and proceeded to probe further.

“Old?” she repeated, leaning back in my lap, to get me into full cinematic view while knitting the little brow in puzzlement. “Why?”

Ah. Well, now. Why, indeed.

Oh, you know, I have a birthday soon, I babbled, weakly. And every year on your birthday, you get another year older.

That sufficed, as she nodded and moved on to other queries. But the question lingered in my heart. Why am I old?

Well, I mean to say, how much time have you got?

I’m old because I recently argued with my sister about the color of a certain pair of gloves in a photograph. Sometimes I argue with her for the mere sport of it, of course, but in this case, I clung to my position like a terrier to an aromatic shoe because of a rare and distinct advantage I hold over her when it comes to assessing color. I have had cataract surgery and she (though older) has not—voila! If you have had the same procedure, you understand the implications with, forgive me, perfect clarity. If you haven’t, well, you might not be old.

Continuing on the visual theme, I suspected I was old when I realized the military-style precision I applied to mapping out strategic geographic locations for glasses. The aforementioned surgery left me requiring only reading glasses, and if you are old enough to need readers, you know they are never where you need them to be, like teenagers assigned to the dinner dishes. If one wants to avoid wandering aimlessly in circles, seeking the pair you just knew was here somewhere, the only solution is to stash a pair at all strategic operating locations—home, office, car, purse, and so forth. I bet you’ve spotted the flaw in this strategy, but I will nevertheless confess it openly, as a cautionary tale for fellow sufferers. Once finished with the close-up task at hand, one must remove the readers and leave them where the map has pinpointed their post. Otherwise, you wind up with four pairs in one room, and none in the critical locations, such as the kitchen, and the wandering begins all over again.

Traveling south of the head for additional evidence, I became certain I was old a couple of months back while folding forward in yoga class. There was a sudden, strange feeling of an unusual obstruction in my right armpit, and further, discreet investigation revealed that my foundation garment (aka BRA) had given up the ghost on one side–perhaps also having reached a certain age. This brazen abdication of responsibility allowed one of the girls, if you take my meaning, to attempt escape, traveling south and east. This distraction did nothing for my yogic calm and meditative concentration.

And so, the litany continues, right? Swapping stories about such things with friends is a part of daily life at our age.

A couple of days after Sis’ question, I leaned over to straighten a photo frame on the wall of my bedroom, where hangs a collection of family portraits illustrating four generations. Still smoldering on the upcoming Big Birthday, I peered more closely at the faces of parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, great-grandparents, and thought about what those people had in common. Most all were people of faith, some to an extreme that annoyed the others, but most went to their graves believing they would meet again. And most didn’t go there early—sturdy, largely healthy, handing down good genes without disorders any more unusual than too great a fondness for Kentucky bourbon. Hard-working folks, all of them, some of them high achievers, some more middle of the road, but all blessed with the will and ability and the freedom to pursue their own paths and support their families. They passed down other traits, as well, like heavy eyebrows, unruly thick hair, lousy hearing, the love of a great joke, and a strong preference for fast cars. Probably, in sum, it’s a story like those of countless families who, with all the warts and inevitable oddities, have been as fortunate as mine.

And there, I realized, is the answer to Sis’ question.

I’m old because I’m lucky.

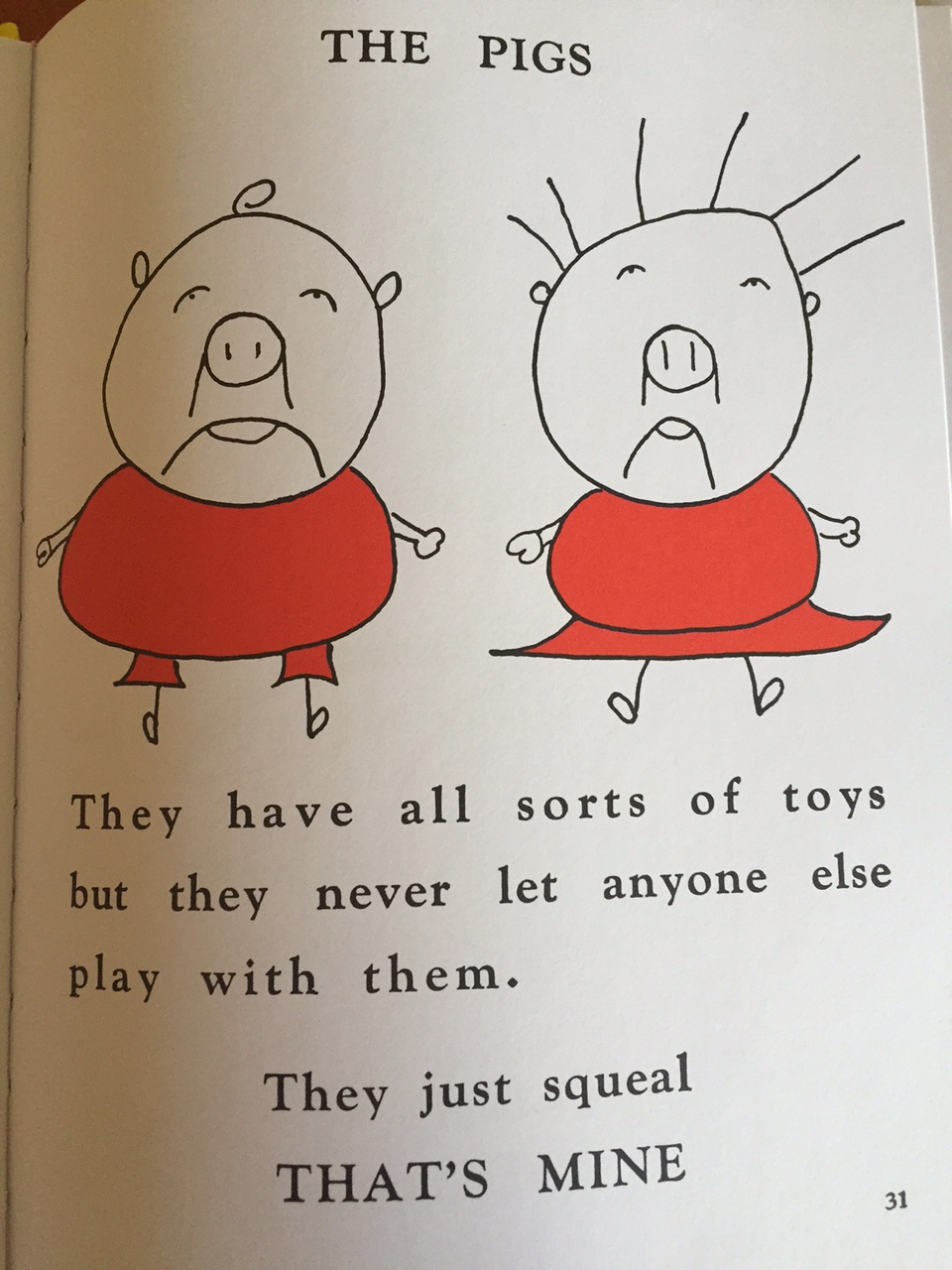

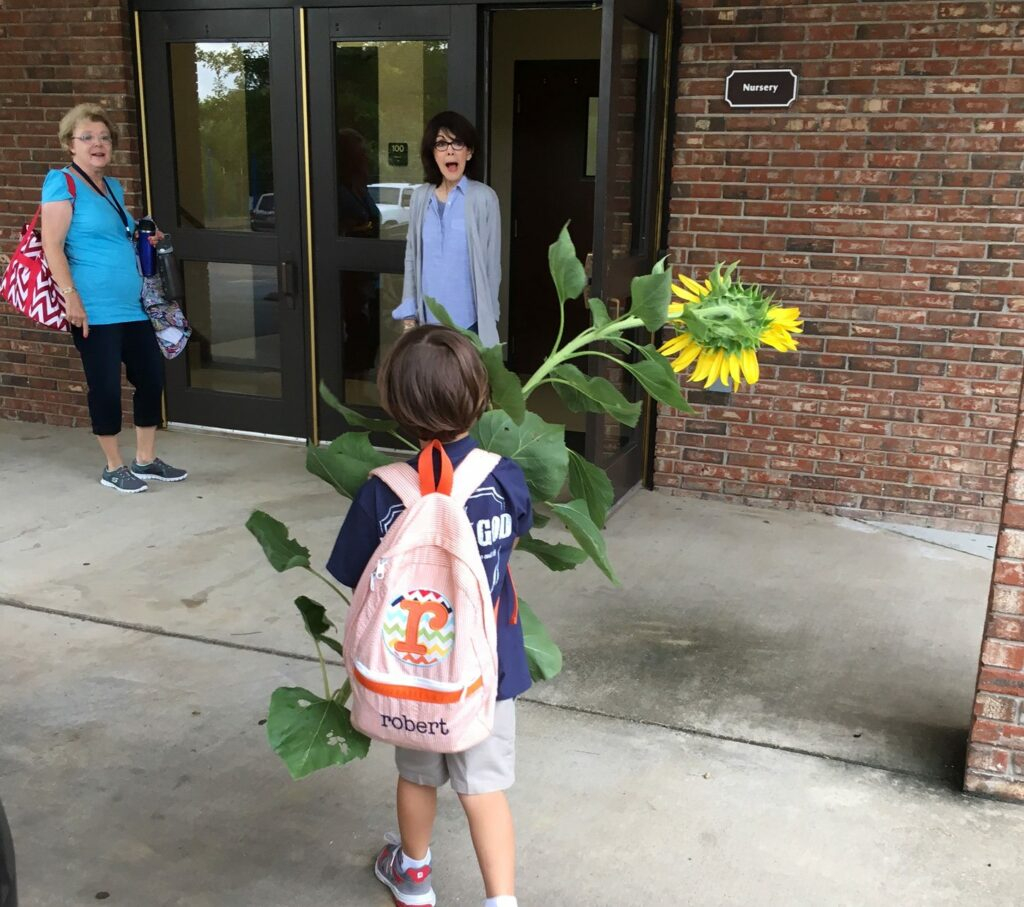

It is a truth universally acknowledged (as the immortal Austen might have put it), that giving stuff to kids is fun.

It is a truth universally acknowledged (as the immortal Austen might have put it), that giving stuff to kids is fun.

the ladies room and missed the inevitable challenge. Her mother reported it went as follows.

the ladies room and missed the inevitable challenge. Her mother reported it went as follows.