It was the kind of answer you pray for when you are on the verge.

“Don’t worry, Mom, I’ll take care of it,” my competent daughter said in response to my panicky text. “I’ll leave in about 15 minutes and will be right over.” I couldn’t find an emoji for desperation, but no matter–she clearly heard it in my silent message.

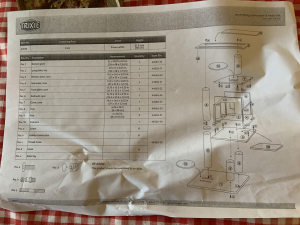

The problem at hand was the assembly of a multi-tiered cat “tower.” With shocking naivete, I had just slit open the box top, dumped out all the parts, and stared aghast at the pile. I pounded on the empty box again, to make sure a lovely, beefy instruction booklet wasn’t stuck down in the bottom. Sure enough, there was only this diagram:

This is it? Letters and numbers only, no orderly Step 1 and 2, no identification on the parts that rolled away when I spilled them out, as if to escape incompetence when they sniffed it. The pudgy dog, loitering nearby and watching closely for my next move, poked his nose in curiosity at a couple of miscellaneous tubular items as they traveled past. My next move was motivated largely by his girth; the whole purpose of the cat tower was to elevate the cat bowl and get it out of the dog’s reach. “Cat food will put weight on him in no time,” the vet had said rather sternly at our last visit, noting my little pal’s gain.

I texted the diagram to my daughter, breathing heavily. What am I supposed to do with just this, I snapped? (No snapping emoji, either, but the steadfast child got the gist.)

Sure enough, this problem-solving female batted not an eye when she sallied through the front door a half-hour later, toting a couple of screwdrivers and the expression of a mountain climber who can see the peak of Everest in view. She scanned the diagram briefly, then commenced with no hesitation. “I love doing this stuff,” she admitted, nary a pause in the flow as she attached this part to that, this bolt with that screw, and a structure began to rise from the floor. How on earth did you learn to do this? I asked, watching from a non-hovering distance. “Just done a lot of these, I guess,” she said. “I think it’s fun.” Skeptical of that last but awash in admiration, I thought back to college apartments, her first home, her addresses since, and wondered how I hadn’t taken notice of this talent. And like a mother so often does, I silently pondered hereditary factors; her father, my ex-husband, is a very handy soul who learned from his highly skillful father. Must have come from that side of her genes, I concluded—she sure didn’t get it from me.

And why didn’t she? I berated myself later, while admiring the cat chomping her dinner quietly on her lofty perch, competition for the meal having been eliminated by its newly elevated location. Why didn’t I ever learn to be handy? Nearly 80 years after Rosie the Riveter and her real-life counterparts labored in Navy machine shops and triumphed as riveters on fight planes, how did I remain dependent on others, often males (before I had a talented adult daughter), for such tasks? Women have broken through in every line of work imaginable; is this the last bastion of masculine domination among the tasks of daily living? How did women my age miss this opportunity?

The answer, which likely surprises no one but me, is many haven’t and didn’t. There’s nothing like an informal Facebook poll to propel you quickly forward into the current moment. I asked my female FB friends to share their experiences with handy work. Then, I sat back and got myself wowed as the comments flowed in with tales of necessity, self-sufficiency, even relaxation. Here’s one:

“My dad had all girls and my Mom was really handy – the two of them just passed on an expectation that we could learn to do all sorts of mechanical tasks. Doing things that involve figuring out how to accomplish a more physical task after working most of my life in roles that required intense concentration has been a relief…My favorite outdoor tool is a chain saw; indoor? Magnetized screwdrivers.”

And this:

“…yeah, I’m handy. Real handy. Tile, wood floors, light fixtures, toilet replacement, LMK when to stop… My dad had me changing tires with him when I was about eight…My ex and I were flat broke trying to raise a family when we were young, so it was either do it ourselves or not get it done. Once I was single that carried on and maybe even increased. My daughter got me a power tools set for Mother’s Day last year. I find it relaxing to accomplish something with my hands since my job only uses my brain.”

A different set of needs, but same outcome. Wow:

“Well, I figured out how to farm. Chainsaws, tractors and implements, fence-building, metal roofing, shed construction, barn repairs, etc. a bit of this and that.”

And finally, the Queen of Handy (unnamed here, but you know who you are) rules all with this testimony:

“I do all kinds of projects…The internet has been a game changer in learning how to do things…I especially like to tile – I’ve done about eight bathrooms, several kitchens, two fireplaces and numerous floors. It’s all math and patterns, things my brain likes. I learned by necessity – limited budget…so I figured out what I could do, what I could learn to do and what I’d need help with…I plan it out in my head, then do it on paper, and then execute. I just spent the last year scraping popcorn off ceiling, texturing, then cutting holes in the ceilings of four bedrooms and the hall, and crawling up in the attic to install the ceiling braces and run the wiring…”

Eight bathrooms? Ceiling braces and wiring? My admiration knows no bounds. Clearly, women have broken through on yet another frontier, and somehow, I missed it. Could there still be time to catch up? I’m shamed, or intrigued, or both, into inspiration. I have no idea what magic may be performed with magnetized screwdrivers, but perhaps the right tools make all the difference. Santa?

The other day I dropped onto the couch in a low moment, staring out the window in despair. I miss my daughter, my grandchildren, all my family, my friends, my co-workers, like we all do, of course. And I realized how fully my heart had finally relented toward this funny little dog when he jumped up next to me, and I encircled him in a crushing hug. I’m SO glad you are here, I told him. I don’t know what I would do, if you weren’t. I’m glad you let people hug you. Your predecessor, rest in peace, would never have tolerated such.

The other day I dropped onto the couch in a low moment, staring out the window in despair. I miss my daughter, my grandchildren, all my family, my friends, my co-workers, like we all do, of course. And I realized how fully my heart had finally relented toward this funny little dog when he jumped up next to me, and I encircled him in a crushing hug. I’m SO glad you are here, I told him. I don’t know what I would do, if you weren’t. I’m glad you let people hug you. Your predecessor, rest in peace, would never have tolerated such.

Leaning carefully her walker as I approached, she accepted my kiss on the cheek, but without preamble for me, demanded, “Where’s Jane?

Leaning carefully her walker as I approached, she accepted my kiss on the cheek, but without preamble for me, demanded, “Where’s Jane?

In the early morning half-light, long before I would routinely switch on bedroom lamps, I drop to the floor in my nightgown to the spot where she is dozing next to my bed. She has never been much of a cuddler, preferring to demonstrate her devotion in other, more dignified ways, but on this day, I am the one who needs a cuddle. I scoot up close enough to wrap my arm around her substantial torso, then withdraw it quickly after my fingertips inadvertently touch the large tumor under her front leg on the opposite side. She does not flinch, but I do.

In the early morning half-light, long before I would routinely switch on bedroom lamps, I drop to the floor in my nightgown to the spot where she is dozing next to my bed. She has never been much of a cuddler, preferring to demonstrate her devotion in other, more dignified ways, but on this day, I am the one who needs a cuddle. I scoot up close enough to wrap my arm around her substantial torso, then withdraw it quickly after my fingertips inadvertently touch the large tumor under her front leg on the opposite side. She does not flinch, but I do.